METALLON

At Galerie Chloé Perrin, Paris. 10/2025.

μέταλλον — Metallon, “Mine” or “quarry” in Greek, root of metal: “a simple body endowed with a particular brilliance…”

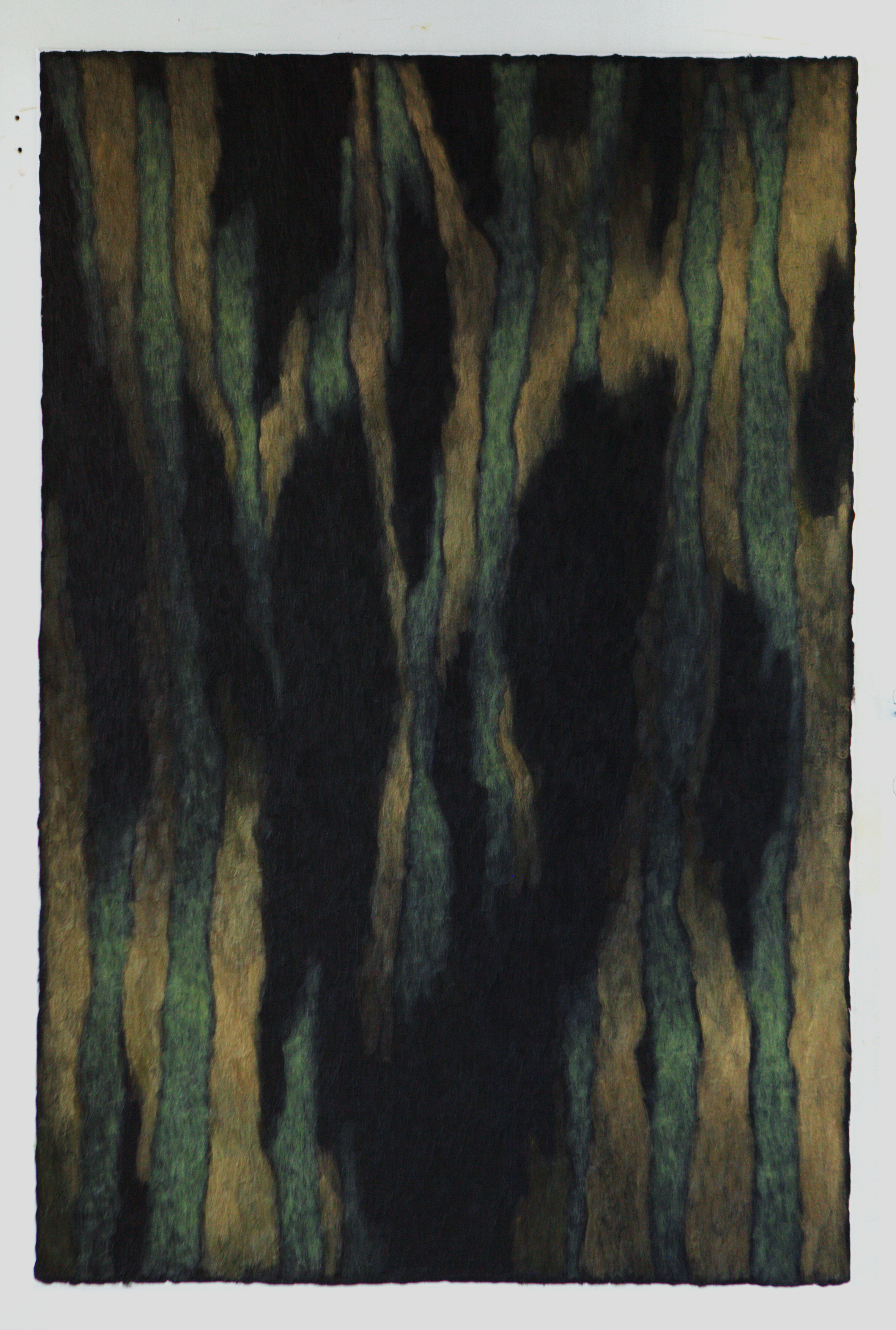

There is something mysterious in Mateo Revillo’s paintings, an ineffable force.

[Text by Eugénie Bey. Read more]

His works do not merely invite contemplation; they absorb us, objectify us. Entering Metallon feels like momentarily losing one’s mastery as a subject, as if the works enveloped us and we began to exist within their very space.

These paintings radiate such presence, such power, that they seem endowed with a gaze of their own. Caught within it, we suddenly find ourselves vulnerable.

Mateo builds his own ruins. His signature lies in this gesture of tearing and rebirth. He cleaves his paintings open, then reconstructs them so that they might unfold, and escape. The great painting here rises and takes flight from its own ruins, within this antique and Parisian interior. Mateo has liberated his painting. It now appears to us in all its lightness and its fracture, like a celestial scar.

Utterly baroque, Metallon is both a structural and emotional torsion. We are immersed in a play of light and shadow. Golden brushstrokes illuminate the opaque, dramatic darkness, a gleam or an ornament? Forms twist and distort; everything moves with gravity and virtuosity.

Everything is in motion. Even the striations seem to dance.

Abstraction is a distant memory. Each motif is alive, each form active; everything shimmers, the matter itself vibrates and comes fully to life.

While Mateo manipulates the forms and structures of his paintings, his stone he leaves untouched. He wished to carve it, but did not dare. This massive black obsidian, brought from the depths of Mexico, gleams and glows of its own accord, finally revealing a Brancusian face, raw and poetic. An Iberian mask.

There is something Malapartian about Mateo Revillo, a nobility and arrogance of old Europe, proudly bearing its drama and its darkness, finding in its own pain and agony the source of its grandeur.

In The Skin, Malaparte unfolds, through a series of tableaux, all the beauty of Neapolitans, and, more broadly, Europeans, ravaged by war. Peace does not liberate them; it enslaves them. Liberation sullied them, for before it, they struggled to survive, and that was noble. What remains to them is the dignity of defeat. For Malaparte, there is nothing worse than victory. Vanquished Europe shines brightest.

In Malaparte, as in Mateo, the ancient, the ruin, and history itself are sanctified, in all their violence and sublimity.

“There is no spectacle sadder, more repugnant than a man, a people, in their triumph. But a man, a people defeated, humiliated, reduced to a heap of broken flesh, what could be more beautiful, more noble

in the world?”

This vision of the world is, in the end, profoundly optimistic. It soothes the turmoil of our time…